Solidarity with the Rednecks!

Benjamin A. Berry

5/19/2024

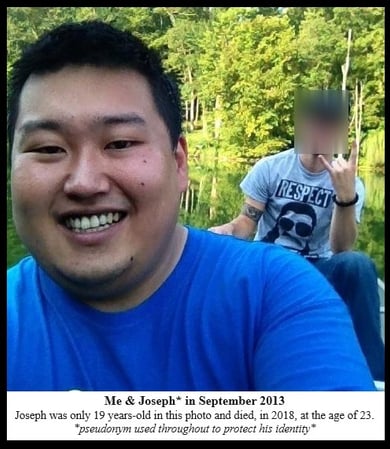

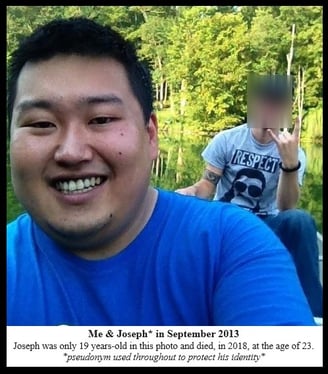

The first person I consciously identified as being from “coal country” here in Kentucky was a young man named Joseph from Pikeville, Kentucky (which he pronounced as “pak-ville” versus my pronunciation of “pike-ville”). Coming from an affluent, private-school-educated background, my first impressions of Joseph were quite ignorant and misinformed: I viewed him as uneducated and, while I’d never use the terms in his presence, associated him with words like “hick” and “hillbilly”. His father was a coal truck driver (which he pronounced as “co-truck driver”) and Joseph’s cultural upbringing, despite being just a few hours from Louisville, differed in many radical aspects from my own. It was only through getting to know Joseph—his background, values, etc.—and learning about the history of the Appalachian region more broadly that I began to understand and appreciate the hidden similarities between us and my own cultural biases.

Joseph’s way of speaking had nothing to do with his intelligence or education, much less his character or moral values. My initial judgement of him and his accent had much more to do with my own prejudices, instilled from my upbringing, and my ignorance of working class culture in Eastern Kentucky. Within a short time of knowing Joseph, I found him to be one of the most genuine, generous, and good-humored people I’ve been fortunate enough to know.

Coming from a family and region dependent on the coal industry, Joseph understood exploitation, struggle, and poverty in ways I’ve never experienced firsthand. His ancestors were of the militant unionists who fought ferociously against the coal bosses and secured important Labor victories for the broad, multiracial working class with the National Miners Union alongside great figures of history like Mother Jones and Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) organizer, “Big Bill” Haywood. Joseph’s forefathers, in Kentucky and neighboring West Virginia, took up arms against Pinkerton goons, police thugs, and National Guard strongmen during historic strikes, aptly adopting the moniker “Rednecks”—so called for the red bandanas the brave unionists wore to identify those on their side in their armed skirmishes with militarized anti-Labor forces.

Joseph grew up in poverty, living in a region rich in history, but severely neglected by the ruling powers of our country after centuries of exploitation—exploitation whereby immense wealth was accumulated for the few on the backs of the many. Joseph understood the principles and values of community, solidarity, and mutual aid, coming from a long line of proud unionized coal miners. However, the history of systemic class oppression, when coupled with the inhumane and atrocious targeting of Appalachia by Big Pharma in the flooding of highly addictive opioids into the most vulnerable communities of the region, did even further damage to the morale, wellbeing, and health of Pikeville, Kentucky and surrounding areas.

Joseph was not spared this hyper-profit-seeking pillaging and found himself, at a young age, struggling with substance use. I met Joseph while volunteering at various recovery and harm reduction centers in Louisville around 2012; his family had sent him here, believing the problems he faced were due to the impoverished region of his upbringing. Unfortunately, the big city of Louisville only added fuel to the fire as Joseph was introduced to even more volatile substances, eventually becoming a regular practitioner of intravenous heroin use. After years of struggle, amassing a few months here-and-there of recovery, Joseph succumbed to his addiction and overdosed on heroin and fentanyl in 2018 at the young age of twenty-three.

Many people, including Joseph’s family—and myself at the time—analyzed the young man’s tragic trajectory and terminus as being a product of “backward” Appalachia, a region popularly characterized as being without hope, opportunity, or a future. While the material conditions of Joseph’s upbringing certainly lend some credibility to this superficial assessment, a deeper investigation quickly observes many of these same trends throughout the country—the world at large, even—and one inevitably sees that the issues which Joseph faced, and countless others currently face, are products of class oppression more than some innate regional moral bankruptcy or shortcoming. Joseph was a working class person from a long line of working class people; in the United States of America, this simple fact is enough to relegate him and those like him to a subhuman classification of commodity. Joseph’s existence was viewed as a single statistic among many in the impersonal evaluation of cost analysis and profit maximization. His death is callously called “collateral damage” or “the cost of doing business” among wealthy CEOs and board members. The exploitation, subjugation, and disregard he experienced is of the same character as those struggling in our inner cities and in far off nations being pillaged by U.S. imperialism.

The misconceptions and biases that I once held against those “backward hillbillies” from Appalachia were instilled in me by design; these notions of the “other” are carefully and meticulously fabricated to keep working people divided from one another. Joseph’s hopes and dreams—to love and to be loved, to live a life of relative safety and comfort, to have his human dignity recognized and honored, to find meaningful, positive, and productive work—these are the same hopes and dreams that all working people have. As fellow working people, we all have so much in common with one another—far more than what might set us apart from one another—and this fact causes the ruling class of owners to tremble; they know, as we, as workers, should know, that what unites us has the power to remake society.

After knowing him for only a few months at this point, Joseph was released from his first treatment center and began living in a halfway house in downtown Louisville. As one of his mentors and as a friend, I would often pick Joseph up on the weekends to hang out and to offer my assistance with whatever he needed. One of these days, he and I were driving down Bardstown Road when he pointed through the window and exclaimed, “Krispy Kreme! Is that where they make those donuts you get at the grocery store?”

“Yeah, one of the places.” I replied, amused by his enthusiasm. “You’ve had a fresh Krispy Kreme before, haven’t you?”

“Nope. Just from the boxes you get at the store.”

I made a quick U-turn and drove through the drive-thru of Krispy Kreme, ordering each of us a piping-hot, freshly-made Original Glazed donut.

When Joseph bit into it, his eyes lit up and he grinned from ear-to-ear shouting, “Holy crap! That’s the best thing I’ve ever eaten! That’s like a spiritual experience in a single bite!”

Aside from being a humorous story, I think this account of simple Krispy Kreme stop best exemplifies the character of Joseph: someone who never needed money or expensive commodities to be happy, someone who could find joy in the simplest of things that most of us ignore or take for granted. I think, too, it’s a story of how all of us are more alike than we are different: because what working class person doesn’t love a fresh Krispy Kreme Original Glazed donut?