The Exploitation of Public Workers

Mark Shepherd

7/9/2024

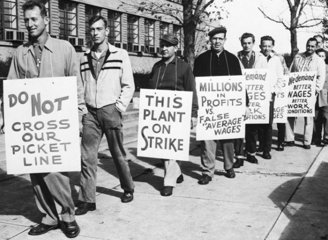

The struggle between the working class and the owning class touches every facet of our lives. From our workplace to the media we consume, the struggle between these two classes is a core aspect of our modern society. Long is the story of the struggle between the workers against the bosses and management. The exploitation of the working class in the private sector is heavily documented and routinely expressed across the country, with all workers having some manner of horror story involving speed-ups, longer work hours, lower real wages, increased disciplinary methods, etc.—all machinations designed to maximize profits for the bosses. It was this clear exploitation that birthed the American labor movement as workers sought to fight back against the unceasing exploitation and oppression they were experiencing in their workplaces on a daily basis.

However, as history and the class struggle have shown us, the exploitation and oppression of the working class is not restricted to any one group, industry, or workplace, with workers of all backgrounds and identities suffering from this exploitation and oppression built into our current economic system. One area where exploitation is “cleverly hidden” from view is the exploitation that public workers experience alongside their private sector counterparts. Though public workers can and often experience the same struggles as their private sector counterparts, the exploitation of public workers differs from that of private sector workers and is even more obscure to the average observer.

The whole existence of a worker in the private sector is to be a profit-maximizing machine, and that's it. The owner of a company understands this, meaning that any policy or action the owner takes will be informed by this perception. Any change in hours, alterations of break times, the placement of workers, etc., are all done with the aim of maximizing profit. From this, the most blatant forms of class warfare manifest, which pits the profit-seeking owner against the workers who are demanding better working conditions and a greater say in the running of the workplace.

In contrast, public workers do not typically experience this open class struggle in their workplaces. The reason for this is that public workers are not viewed as profit-maximizing machines by their bosses because the “Boss” is not clearly identified. The vast majority, if not all, of the money that social services receive comes from tax money, which is distributed according to a budget. As such, the labor of the public workers is based on their ability to facilitate the day-to-day operations of social services. Yet, like their private sector counterparts, public workers are still exploited.

The first issue that public workers face is that there is no federal law similar to the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) that provides any protections or rights to public workers. Without an NLRA of their own, public workers are subjected to different rules that are determined by state and local governments, resulting in a patchwork of even more complicated labor laws that create different material conditions for public workers.

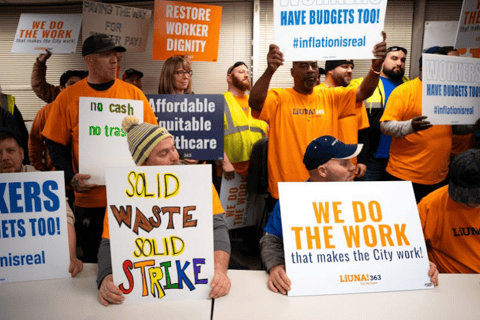

Secondly, in Louisville, public workers are legally barred from striking in any situation. This means that a strike, a powerful tool employed by private sector workers to achieve their demands, has been snatched from the public workers in Louisville. The result is that unionized public workers are limited in the tactics they can use to achieve their demands. This has been the case with the TARC drivers with the Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU) Local 1447, who could only host a “practice picket” and community demonstrations to spread their message; there were still members of ATU Local 1447 working during the demonstration since they couldn’t legally go on strike to join their coworkers. In other states and cities, there are similar rules against public worker strikes, even in the states that do provide public workers certain protections.

Thirdly, public workers suffer from the “industrial complex” that social services inevitably develop with the presence of bureaucrats. In many social services, these bureaucrats will receive unprecedented levels of pay while the workers receive far less. For example, Kentucky has some of the lowest-paid college/university professors in the country, but boasts some of the highest-paid administrators. In all workplaces, the workers do the labor, know the most about their jobs, and commit the most themselves, meaning that they should get the lion's share of the pay and benefits. After all, without these workers, who will do the job? Conversely, though, we see that an industrial complex develops in which the administrators justify their existence by creating more bureaucracy that gums up the work of the workers, but also serves to redirect often limited funds toward the offices of these bureaucrats. So, not only do the workers not get the money they deserve, but the offices or departments they run also suffer, which affects those who depend on them. With any complicated system of organization, there will need to be people tasked with managing and monitoring things to keep everything moving smoothly; however, while this work is important in its own right, the insane pay that some bureaucrats get for these jobs in relation to the pay that workers receive is indefensible.

In addition to lower pay and cuts in needed funding, public workers and the public services they facilitate are under constant threat of being privatized. With the owning class being driven by an insatiable hunger for ever greater profits, they constantly seek to create markets that will generate more profit; in this, public services are desirable prospects, as they represent an “untapped pool” of potential profit. So, the owning class will use whatever means available, such as lobbying and funding certain politicians, to secure greater access to this “untapped pool” until, eventually, the public service has all been privatized. Privatization can come to any public service, whether it be USPS or K-12 education. Sometimes privatization hurts public workers by causing them to lose their jobs; in other cases, they may keep their jobs, but face worse pay, benefits, and security. Privatization hurts the general working class as a former public service is now locked behind a pay wall, limiting which workers and communities can have access to the new for-profit service, thereby harming the working people who depended on the former public service.

Many public workers are organized, with the TARC drivers being organized with ATU Local 1447 and the library workers at the Louisville Free Public Library being organized with the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) Council 962. Being unionized is an important step for these public workers, but there is so much more that they need. In addition to the usual demands of better pay and working conditions, all public workers need to have their own version of the NLRA on the federal level to guarantee them the rights that their private sector counterparts already have, with both groups deserving a “Protect the Right to Organize” Act (or PRO Act) to further strengthen their power as working people. In addition to having their own NLRA, public workers should have the right to strike. With the right to strike, public workers can engage in work stoppages that force the bureaucrats and decision-makers to agree to the workers’ demands; after all, the bureaucrats are not the ones keeping everything running; it’s the workers. And finally, there must be a clear push from unions, workers, and their community supporters to cut through the top-heavy fat infesting our public services and to create barriers to protect against privatization. There should be no reason for an administrator to receive an exorbitant amount of pay so much larger than a rank-and-file worker, nor should a public service be sacrificed for the owning class to profit.

The principal area of conflict in which the class struggle manifests most blatantly is the private sector because of the size of its operation compared to the public sector and because of the profit-motive that private sector workers have to struggle against. Nonetheless, as stated in the beginning, the class struggle is everywhere. Just because UPS is more likely to be an area of fiery class conflict than a public library doesn’t invalidate the struggles of those library workers. The exploitation of public workers differs from that of private sector workers, but one thing unites them: they are both exploited and oppressed. All sections of the working class experience exploitation and oppression, necessitating an unparalleled level of solidarity between them all to fight as a united class against the owning class.

Public workers are the ones whose labor makes social services function. Without them, like any worker in any other workplace, nothing gets done. These social services, such as public transportation, are the lifelines for so many working people, so when public workers are exploited and oppressed, it's not just them who suffer, but the millions of workers who depend on their essential labor. In this situation, the shared struggle of public workers and private sector workers is most apparent and should serve as a bridge of unequivocal solidarity between them. United under the banner of the working class, public workers and private sector workers can fight for their shared empowerment and liberation.